The care team, including (left to right) nurse Kyle Breitenstein, respiratory therapist Melissa Delavara and nurse Hannah Peterson, prepare to move a patient to the prone position.

In February 2020, Hilary Babcock, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and a specialist in infectious diseases, gave a talk at a conference in Yokohama, Japan. From her hotel window, she could see the gleaming white cruise ship, the Diamond Princess, docked. At the conference breaks, local doctors talked to her about how they planned to care for COVID-19 patients from the ship.

She helped them strategize, but she was cold with dread. This was a brand-new virus, and Babcock, medical director for infection prevention and occupational health at BJC HealthCare, knew it would spread like wildfire. No one was immune. No one was protected.

A week after she flew home, Washington University sent word to all overseas students and faculty to return to the United States. Babcock focused on ways to keep health-care workers safe while they cared for patients. “That rapidly became much more complicated,” she said, because the personal protective equipment (PPE) they needed was in short supply. “For everything we looked at — even IV tubing, saline, commonly used drugs — there were shortages.”

After talking with friends in Italy, where the hospitals were aflame with the virus, Tiffany Osborn, MD, MPH, professor of surgery and of emergency medicine, had bought herself some extra PPE online. Better to have and not need, she thought. Then the virus exploded in New York.

Daniel Theodoro, MD, MSCI, assistant professor of emergency medicine, had trained there, and several of his former colleagues fell ill, one ending up on a ventilator. Theodoro was terrified; he has young children at home. “The only other time I was this scared was while I was on shift when the Twin Towers came down,” he said. “I was privy to the radio transmissions, and there were all these rumors in the fog of war … . That is the only thing equivalent to the panic that was coursing through our veins daily.”

In those early days, “it felt that if you were to walk through a plume of COVID cough you’d end up dying and contaminating your entire family,” Theodoro continued. He kept seeing photos of Chinese physicians covered head to toe in plastic — and here he was, making an N95 mask last for days when normally, he would have discarded it after one interaction with a patient.

Even tests were in short supply. “Ideally you would want to be able to test anyone you think might have it,” Babcock said, “but at the beginning, across the whole country, the testing was so limited. That made it very hard to get our arms around how many cases there really were. And we didn’t yet know how much of an issue asymptomatic transmission was going to be.”

Rodrigo Vazquez Guillamet, MD, and Cristina Vazquez Guillamet, MD, play with their sons in Forest Park. While taking shifts in the ICU this past spring, the doctors made the difficult decision to stay in the Knight Executive Education & Conference Center on the Danforth Campus to protect their sons and Cristina’s parents — who help with child care — from COVID-19 exposure.

Cristina Vazquez Guillamet, MD, assistant professor of infectious diseases and pulmonary and critical care medicine, and Rodrigo Vazquez Guillamet, MD, associate professor of medicine in the pulmonary and critical care division, felt an impossible pressure: “We cannot be on the sidelines of this. It is our duty. But we cannot risk the lives of our little boys” — or of Cristina’s parents, who live with them and help with child care.

They decided to stay at the Knight Executive Education & Conference Center on the Danforth Campus, which was swiftly converted into a hotel for health workers. This way they could focus, starting work before 7 a.m. and ending after 7 p.m. Then they’d strip off their PPE and race back to the hotel to shower and Facetime their little boys — this was the first time they had ever been parted — before the boys’ bedtime.

Cristina had always wondered about the bond between soldiers; now, joking with the nurses as they checked each other’s PPE for a tight fit, she felt what she imagines is the same camaraderie. But she also felt a consuming fear. “Women don’t seem to get as sick,” she told Rodrigo. “I think I should take the ICU shift for both of us.”

“Are you out of your mind?” he shot back.

There was no guarantee of safety anywhere. “You’re staring your mortality in the face,” said Brent Ruoff, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine. “Especially those of us over 60 — we can kind of stuff that down internally, but it did create stress.” His older brother has disabilities, and Ruoff takes care of him. He called their sister and let her know that if worst came to worst, she might have to take over.

Staying safe

As the days went by, though, it became clear that the PPE, tightly rationed as it was, worked. “At first I would gel (sanitize) about 50 times just taking my shirt on and off,” Theodoro admitted, laughing. “Now I’m like, unless someone came in here and licked the counters, I’m probably OK.”

The emergency department, after all, was the proving ground. These were the docs doing triage, testing, often intubating before sending the patient upstairs. And in all this time, said Rob Poirier, MD, assistant professor of emergency medicine and clinical chief of the department, there has not been a single case of transmission between or among patients and staff.

Health-care workers write a message of support on a wall facing a patient’s room in a COVID-19 ICU.

Precautions were stringent throughout the hospital, and they saved lives, but they came at a cost. “The distancing really affects me,” said Ken Remy, MD, MHSc, MSCI. One of the nation’s few adult and pediatric intensivists, he spent significant time on COVID-19 international response teams advising various international ICUs. Early on, he spent practically “more time than anybody” in the COVID-19 ICUs across the BJC network because of his adult and pediatric expertise — despite a preexisting condition, a worried family, and multiple showers a day. But what he could not bear was the isolation. Nurses would write “You are loved” on the glass so a patient could see it the minute they woke, but the only way they could see loved ones was on an iPad the hospital supplied (and med students taught families how to use).

The no-visitors policy eased to one visitor in late June. By then, Rodrigo Vazquez Guillamet had listened to a 20-year-old sobbing because her mother was dying, and she could not even say goodbye in person. “Look,” he said to senior administration, “we have to keep our humanity through this.”

So they changed the rule. “And we were so grateful,” Cristina said.

“The one thing nobody could predict when it was really at the peak, was how relentless it would be. How tired you would be. It just. Didn’t. Stop.” — William Powderly, MD

She also was deeply gratified by all the collaboration. Physicians from unrelated specialties, pulled from their own research or clinics for safety’s sake, pitched in — dermatologists staffing the COVID-19 call line, cardiologists and pulmonologists volunteering to work in the COVID-19 ICU, nephrology researchers making DIY hand sanitizer for the dialysis centers, med students designing face shields.

New information came daily, and what was useful had to be sifted from speculation, anecdote and politicized federal guidance. “The texts and emails began before 6 a.m.,” said Michael Lin, MD, associate professor of medicine and interim chief of hospital medicine. “Then it was all about trying to respond and anticipate staffing needs, clinical needs, PPE, cleaning supplies, work space distancing, provider wellness — through close to midnight. Things were being done on the fly — there were changes even from morning to night in the recommendations and the staffing. It really was building a plane while you are flying it.”

Among those in the control tower was William Powderly, MD, FRCPI, the Dr. J. William Campbell Professor of Medicine, Larry Shapiro Director of the Institute for Public Health, director of the Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences, and co-director of the Division of Infectious Diseases. He had never had to multitask with an urgency this intense. Still, every day he pried himself away from the administrative work, donned a mask, and went to talk with fellows and trainees who were seeing patients. “It reminded me of why I was doing this,” he said, “and it grounded me.”

One of the many bits of information he captured was how often patients lost their senses of taste and smell. “That wasn’t written anywhere yet; it wasn’t in the CDC protocols. But we put it into ours, because it made biological sense, and we were hearing it from a significant number of patients, as many as 10%, and for quite a few, it was their only symptom.”

The daily trick, clinically, was to balance caution and resolve, staying patient but learning constantly. “The one thing nobody could predict,” Powderly said, “when it was really at the peak, was how relentless it would be. How tired you would be. It just. Didn’t. Stop.”

Charge nurse Caroline Becker cares for a COVID-19-positive patient.

Exhaustion and exhilaration

“As stressful and scary as the initial days were, it was an exciting time, because everyone was sharing information,” said Colleen McEvoy, MD, assistant professor of medicine. Protocols, clinical observations, research findings, and ideas flew between institutions, and the experts at WashU offered guidance to public health departments and other hospital systems. “The whole focus was the patient and the disease,” McEvoy said, “and that’s why we got into medicine. That’s why we could work 14- and 15-hour days.”

They worked those days for months, though, many without a weekend off, and administrators heard zero complaints. “There was very little evidence of ego,” Powderly said. “People just knuckled down to solve the problems.”

McEvoy and Osborn became co-directors of the COVID-19 Critical Care Task Force, anticipating scenarios and creating guidelines. Which treatments might heighten contagion? High-flow oxygen could keep the lungs open, but it would send air into the room, but new data showed that when the person wore a mask, that extra exposure was virtually canceled out. They talked, at all hours of the night, with colleagues around the world and on the coasts. Those anesthesiologists who were no longer in the OR because elective procedures had been canceled? Put them on a procedures team, docs in Seattle suggested, so they can intubate and put in central lines while the pulmonologists deal with ventilators. The common wisdom at the outset was to rush to intubate, but that turned out to be unnecessarily aggressive. “Normally, I’ll intubate one or two people every month,” said Theodoro, “and colleagues in New York were intubating one or two an hour.”

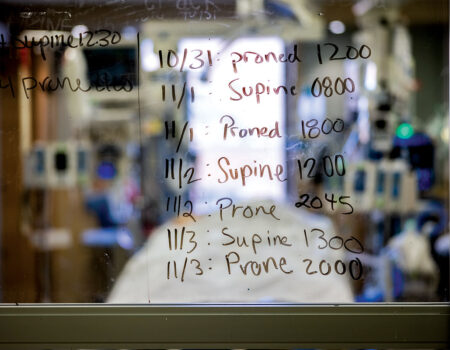

Physicians gathered up practical bits of guidance wherever they could. Proning helped, said Remy, because when patients rolled over to lie on their stomachs, the bottom of the lungs could fully expand. Clotting was a special danger; blood flow was key, and the linings of arterial vessels could inflame. Lungs of COVID-19 patients were not heavy and wet, as they are with influenza, but supple — that was odd — and patients with extremely low oxygen saturation sat there playing on their phones, not even short of breath. Some patients only had neurological symptoms, like dementia; could that be what had happened to the New York physician whose suicide haunted everyone? Or was she just worn down by the trauma of all she had seen?

Societal complications

St. Louis waited, nerves on edge. But thanks to weeks of meticulous planning, the ED and six COVID ICUs managed incredibly well, even when cases were at all-time highs. And by the end of April, the first surge began to come down.

Over time, the COVID-19 teams developed a good sense of how to take care of these patients. They also knew how to stay safe, so personal fears were easing — but social tensions were ratcheting up, the heightened anxiety and despair creating a bleak landscape.

“Since COVID-19 started, our community violence rate has dramatically gone up,” said Poirier of the emergency department. “The number of people shot has gone up 30% to 50%, and there are more suicides and suicide attempts and more drug-related issues, sometimes in people with two, three, even four different drugs in their system at once.” People without homes were insisting they could quarantine under a bridge and tell people to stay away.

“It kind of feels like the four horsemen are riding into town,” Ruoff remarked to a colleague.

Physician assistant David Schlictman, PhD, (left) and pulmonologist Praveen Chenna, MD, discuss a chest X-ray.

Nationwide, doctors began expressing concerns that the CDC, which always has been a steadying voice of authority, seemed to be delaying or changing its guidance due to political pressures. “You had to sift through recommendations that were coming out of Atlanta and D.C. and try to understand what the different pressures were,” Powderly said. “We’re fortunate in that quite a number of the infectious disease faculty have held national leadership positions, so we know quite a number of people at the NIH and CDC. That allows us to have a better understanding of the dynamics.”

Still, there was no looking things up. The textbooks on COVID-19 had not yet been written. The only way to move ahead was to let the virus itself teach them.

Another intersection of society and medicine was the disproportionate number of patients who were African American. It was surreal enough to see an entire ICU filled with patients who had only one kind of sickness, Cristina Vazquez Guillamet said, but then to see that the majority of them were Black, more vulnerable for a long list of reasons laced with mistrust and inequity? “We have to do something about this,” she told Rodrigo. “At the end of this, we have to be better humans.”

That was the impulse that brought WashU docs outside, the sun reflecting off hundreds of white coats as they lined Kingshighway Boulevard, protesting for racial justice after a police officer in Minneapolis knelt on George Floyd for more than eight minutes while he gasped, “I can’t breathe.” Asked by a USA Today reporter if protesting was a public health risk, Babcock pointed out that systemic racism is also a public health risk. Will Ross, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and associate dean for diversity, co-authored a study that found African Americans to be 16% of the region’s population — and 34% of its confirmed COVID-19 cases.

A new and lethal pandemic, grueling hours, wrenching isolation, social tension — what has kept WashU’s docs going all these months? A fierce sense of mission, of responsibility. This was what they had trained to do, what they could do when others couldn’t. Also, notes Cristina Vazquez Guillamet, “there was the intellectual curiosity. We wanted to understand.”

What was hard was risking your life and your family’s, witnessing so much suffering and sacrifice, then hearing people insist that the virus was a political exaggeration, the precautions a conspiracy. “People find out you’re a doctor, and they want you to tell them, ‘Yeah, it’s nothing,’” Theodoro said. “When you say, ‘No, I’ve seen it,’ the incredulity — it can’t register.”

At the bedside, though, all denials and arguments and alternate realities vanish, and only care remains. “When you look at a patient, you don’t see their political views,” said McEvoy. “It doesn’t matter if they thought COVID was real or not.”

Published in the Winter 2020-21 issue

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Email

Email